Treatment of CVS

Although limited data exist on treatment outcomes in children and adults with CVS, a NASPGHAN (North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition) consensus statement released in 2008 has outlined guidelines for management of CVS in children based mainly upon pediatric case series. A consensus statement for management of adults with CVS has yet not been released, but a medical committee of ten medical professionals has been formed to develop guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of CVS in adults.

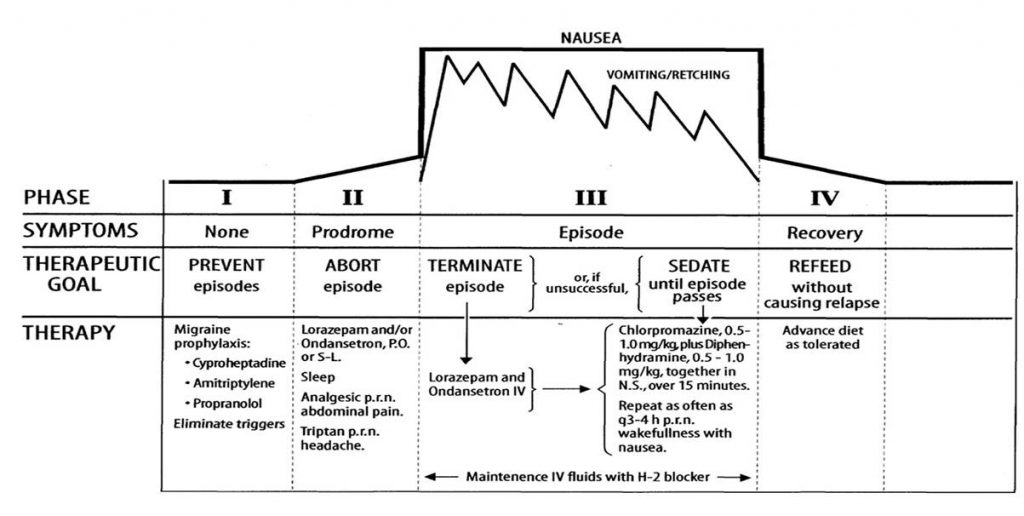

The clinical course of CVS can be divided simply into the episode phase and the well phase, during which the person returns to his or her normal or baseline state of health. The episode phase is further divided into the prodrome as the person becomes ill up to the point at which vomiting begins, the vomiting phase, and the recovery phase during which the vomiting ceases and the person returns to baseline health. Each phase has therapeutic implications.

1. The goal of the inter‐episodic phase is prevention of episodes.

2. The goal of the prodromal phase is to abort the vomiting phase.

3. The therapeutic goal during the vomiting phase is termination of the nausea and vomiting or, if this cannot be achieved, sedating the patient until the episode passes; deep sleep makes the vomiting cease and makes the patient insensible to the misery of the attack.

4. The goal of the recovery phase is resumption of oral intake without causing a relapse of nausea and vomiting.

Effective medical care of CVS patients has at least five elements:

1. Continuity of care by a caring physician who is familiar with CVS and who is accessible and responsive to the patient, especially during attacks.

2. The availability of effective medications, e.g. prophylactic agents, antiemetics, anxiolytics, analgesics and sedatives.

3. There must be a rational plan for the deployment of effective medications.

4. Promptness in the clinician’s response to the acutely suffering patient is itself therapeutic; long waits in treatment facilities are counter‐therapeutic for patients in severe distress.

5. A “default procedure” of sedation is needed to relieve the misery of an episode that has failed attempts to prevent, abort, or terminate the attack.

Prophylactic therapy

Avoidance of known triggers can reduce the frequency of episodes. Dietary triggers may include chocolate, cheese, monosodium glutamate, nitrites, and caffeine. Lifestyle changes include avoidance of anxiety and excitement triggers as well as energy-depleted states that can be induced by sleep deprivation, fasting, illness, and physical overexertion. Those with high-energy demand or a history of fasting-induced episodes can benefit from high-carbohydrate snacks between meals, before physical exertion, and at bedtime. In some cases, stress management strategies with the aid of a psychologist can attenuate the effects of excitatory or negative stressors as well as reduce the fear and anticipation of future episodes.

Daily use of prophylactic medications is based upon empiric therapy that is traditionally employed to treat other disorders, including migraines, epilepsy, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and birth control. Prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have episodes that are frequent (more than 1 episode per month), severe (prolonged for more than 3–5 days), debilitating (associated with hospitalization), or disabling (causing absence from school or work). Prophylaxis is also recommended for those who fail a trial of abortive therapy or supportive measures. The ultimate goal of prophylaxis is to prevent attacks altogether but, at the very least, to reduce the frequency, duration, or intensity of episodes.

Tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) have been shown to be effective in treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome with amitriptyline recommended in a step-up approach for treatment of adults with cyclic vomiting syndrome. If amitriptyline cannot be tolerated, TCAs with fewer side effects can be initiated.

Prophylactic antimigraine medications such as propranolol can be considered, especially in patients with a personal or family history of migraines.

Pharmacological treatments for CVS are the focus of ongoing research. Some patients with CVS are already using agents purported to improve mitochondrial function. L-Carnitine is an amino acid-like compound whose primary function is to transport long chain fatty acids into mitochondria for oxidation. Oral L-carnitine has been reported to reduce the frequency of CVS attacks in some cases. Co-enzyme Q10, a hydrophobic substance, serves as an electron carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain and as an antioxidant.

Prophylactic medication

- Cyproheptadine

- Pizotifen

- Diphenhydramine

- Propranolol

- Amitriptyline

- Nortriptyline

- Imipramine

- Lorazepam

- Phenobarbital

- Topiramate

- Valproic acid

- Gabapentin

- Zonisamide

- L-Carnitine

- Coenzyme Q-10

- Phentolamine

- Dexmedetomidine

- Zonisamide

- Levetiracetam

Data from Empiric Guidelines for treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome (Fleisher, 2008),

NASPGHAN consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of CVS (2008),

Handbook of gastrointestinal Motility and Functional Disorders (pp 131-140) (2015),

CVS in Adults (Abell et.al, 2008),

CVS in 42 adults: the illness, the patients and problems of management (David R. Fleisher et.al, 2005),

Adult Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Successfully Treated with Intranasal Sumatriptan (2009).

Abortive therapy

Abortive therapy is intervention taken at the onset of an episode or even earlier during the prodromal phase, ideally to abort the vomiting phase altogether or reduce the duration or severity of the episode. Abortive therapy should be considered for those who have sporadic episodes that occur less than once per month and who prefer not taking prophylaxis or those who have breakthrough episodes while on prophylaxis. As patients with intractable emesis are unable to tolerate oral medication, these medications usually must be administered parenterally or via rectal preparations.

The primary CVS abortive agents include 5-HT 1B/1D agonists commonly used for migraine headaches. Management of an episode after it has started (‘abortive treatment’) includes keeping the patient in a dark and quiet room, intravenous hydration, ondansetron, sumatriptan, clonidine, and benzodiazepines. Clonidine shortened episode durations for some patients from 4–5 days to 16–48 h in combination with a low dose IV midazolam infusion but also in combination with other drugs.

Prophylactic treatment includes cyproheptadine, propranolol and amitriptyline.

Supportive care

Supportive care is used whenever intractable symptoms continue during an episode that fails to respond to abortive therapy. If the emetic phase cannot be aborted, it should be treated without delay, preferably within an hour of onset. “Watchful waiting” or long waits in treatment facilities are counter-therapeutic.

Treatment of patients whose episodes last days rather than hours is best done by direct admission to an inpatient setting. The experiences of sick cyclic vomiting patients in crowded, noisy emergency departments are generally unsatisfactory, and there is little or no long‐term continuity of care. Emergency Department physicians know the formidable differential diagnosis of vomiting, but if they are unfamiliar with the patient’s history or with CVS, they are likely to order redundant diagnostic tests, further delaying relief of the patient’s symptoms.

Typical treatment consists of re‐hydration and antiemetic medication, after which the patient may be sent home before the attack has run its course. Many are forced to return to the Emergency Department where they may encounter personnel who are busy caring for the critically ill or injured and may be less responsive to the cyclic vomiting patient’s misery.

In general, ongoing management of functional disorders is an unwarranted imposition on Emergency Departments. The hours patients may spend in Emergency Department waiting rooms delay or prevent effective care for those in the vomiting phase of CVS.

Supportive care includes intravenous fluids, non-stimulating environment, antiemetics, analgesia, and sedation. If nausea fails to clear, or if it subsides only to return within a short time, the only way to relieve the patient’s distress is by sedation, which should be continued until the emetic phase passes. Deep sleep stops vomiting that originates in the brain and makes the patient insensible to nausea and other distress.

Ondansetron, a 5-HT3 antagonist, is primarily used as an antiemetic, with efficacy rates around 62%. More effective at the higher dosing of 0.3–0.4 mg/kg per dose. (This is twice the dose recommended for chemotherapy patients.) Ondansetron generally reduces both nausea and vomiting but rarely aborts an episode. The addition of lorazepam provides sedation that may lessen intractable nausea.

When all else fails, intravenous administration of a combination of chlorpromazine plus diphenhydramine can cause effective sedation. Previous experience suggests that phenothiazine antiemetics (D2 antagonists) have poor efficacy in this disorder, even less than placebo responses, suggesting that dopaminergic pathways are not involved.

Intravenous opiates are necessary for pain control in some patients. However, they should be made aware of opiates’ anxiolytic effects and the potential for dependence when opiates are used indiscriminately for anxiety as well as abdominal pain. Symptoms of opiate withdrawal, e.g. irritability, restlessness, nausea, cramps, insomnia, anxiety, may be misinterpreted as those of panic and/or the prodromal and emetic phases of CVS.

Interepisodic nausea and anxiety, common in adult CVS, can also benefit from supportive care during the interepisodic phase, including antiemetics and antianxiety agents. Abdominal pain that persists after the acute attack may require tramadol or other non-narcotic analgesics. A very small subset unfortunately may require narcotic use between episodes. Co-management with a pain specialist is recommended for these individuals.

Abortive and Supportive medication

- Ondansetron (Zofran )liquid, tablets or ODTs (oral disintegrating tablets) at 0.3 – 0.4 mg/Kg/dose. NB! This is twice the dose recommended for chemotherapy patients.

- Aprepitant (Emend), 80 mg, may be used alone or with Zofran, although it is about twice as expensive as Zofran

- Promethazine

- Diphenhydramine

- Palonosetron

- Dolasetron

- Granisetron

- Prochlorperazine

- Lorazepam: (Ativan) is anxiolytic, anti-emetic and promotes sleep. It works well together with ondansetron. Lorazepam tablets are almost tasteless and dissolve in the mouth without the patient having to drink.

- Alprazolam: If the predominant prodromal symptoms are those of acute anxiety (e.g. chills and/or hot flushes, sweating, trembling, palpitations, pounding heart, dyspnea, light headedness), alprazolam, which is a rapidly acting anxiolytic, 1 to 2 mg p.o. taken immediately, may abort the anticipated vomiting.Opiates that reduce anxiety seem to be the only agents capable of relieving this panic.

The first step toward overcoming panic‐induced CVS requires that patients’ attitudes change from feeling out‐of‐control to feeling in‐control by having something they can do to protect them from the onslaught of a CVS episode. Having the ability to promptly relieve the panicky feelings associated with CVS attacks is therefore a crucial element in their management

Failure to quell prolonged panic results in ongoing suffering which, in turn, promotes anticipatory anxiety and coalescence of CVS episodes.

- Clonidine

Clonidine shortened episode durations for some patients from 4–5 days to 16–48 h in combination with a low dose IV midazolam infusion but also in combination with other drugs.

- Ibuprofen

- Tramadol

- Ketorolac

- Morphine

- Fentanyl

- Dilaudid (3mg at a dose of about 0.08 mg/Kg/dose by rectal suppository.)

- Oxycodone may be required to help induce sleep and control the pain.Oral or intravenous opiates are required to control abdominal pain in some patients. However, they should be made aware that opiates are anxiolytic as well as analgesic and that opiate dependence is likely if opiates are used indiscriminately to relieve anxiety as well as pain.

Symptoms of opiate withdrawal (e.g., irritability, restlessness, nausea, cramps, insomnia and anxiety) may be misinterpreted as being due to panic and/or the prodromal and emetic phases of CVS.

- Ibuprofen

- Sumatriptan (by tablet or nasal spray)

- Zolmitriptan

- Frovatriptan

- Prilosec

- Prevacid

- Ranitidine

- Pantoprazole

- Omeprazole

- Loperamide (Imodium)

- Hyoscyamine S-L

- Propranolol (Inderal), 0.1 – 2.0 mg/Kg/dose p.o., may lessen these effects.

- Diphenhydramine combined with Chlorpromazine

- Lorazepam

Data from Empiric Guidelines for treatment of cyclic vomiting syndrome (Fleisher, 2008),

NASPGHAN consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of CVS (2008),

Handbook of gastrointestinal Motility and Functional Disorders (pp 131-140) (2015),

CVS in Adults (Abell et.al, 2008),

CVS in 42 adults: the illness, the patients and problems of management (David R. Fleisher et.al, 2005),

Adult Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome Successfully Treated with Intranasal Sumatriptan (2009).

Use of intravenous midazolam and clonidine in cyclical vomiting syndrome: a case report.Palmer GM1, Cameron DJ. 11 January 2005